As Seen on TV in the Fifties:

Elvis on the Living Room Screen

Karal Ann Marling provides one of the best breakdowns of Elvis on TV in the fifties in her 1994 book, As Seen on TV: The Visual Culture of Everyday Life in the 1950s. The volume covers the whole gamut of fifties culture from Betty Crocker to Disneyland, but of particular interest is Chapter 5, entitled, "When Elvis Cut His Hair: The Meaning of Mobility."

Marling was then a professor of Art History and American Studies at the

Marling was then a professor of Art History and American Studies at the University of Minnesota. Unlike the intellectual tenor of many academic Presley studies, Marling's text flows easily. Occasionally she engages in a form of intellectual alliteration, but for the most part Marling presents her views in terms easily understood by the general reader. And Elvis fans will be pleased to find that Elvis is presented in a positive light throughout the chapter.

Marling was then a professor of Art History and American Studies at the

Marling was then a professor of Art History and American Studies at the As the title of the Elvis chapter indicates, Marling focuses initially on Presley's hair. In the chapter's opening paragraph, she claims that in the fifties he was known "as much for his rococo pompadour as for his pelvic pulsations and rock 'n' roll music." (I can vouch for that. At age seven I knew who Elvis Presley was, not because of his music or stage antics, but because he was "that guy with the sideburns.")

Marling begins at the end with Elvis's clipped hair falling on the floor of an army barbershop in 1958:

"Back in '58, teen legend had it that Elvis actually tooled up to his Army physical in a great big Cadillac convertible, with a Las Vegas showgirl snuggled up beside him, his ducktail rippling luxuriantly and defiantly in the breeze. But later rock critics and historians view the raining morning of Elvis Presley's induction as the beginning of the end. Playing Delilah to young Presley's Sampson, the Pentagon cut off his hair and thus delivered him up to the Philistines."

The story then jumps back to the mid-fifties, when hair was a focus of identity for many young people in the post-war years. "In teenagers of both sexes, the protest against the inevitable coming of age was liable to go straight to one's head," Marling notes. She describes Elvis's hairdo as the kind that "made decent men cringe and maidens yowl: it flopped and fluttered and fell across his face, requiring constant adjustment … There was something perverse about boys who fussed with their hairdos like girls, although the young Elvis Presley was by no means the first teenager to seize on a hirsute symbol for generational rebellion … "

Presley insiders in those early years recall seeing him stand in front of a mirror, combing his hair over and over again until every strand was perfectly located and locked in place. Marling contends, though, that Elvis's hair was never intended to stay neatly groomed.

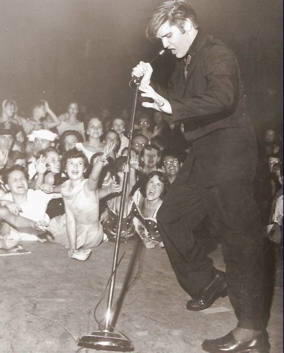

Disheveled hair was Elvis's visual signature "Presley's hair was almost never neatly coiffed," she insists. "The first barrage of Elvis Presley photos, published by the picture weeklies in the summer of 1956 … used his disheveled hair as a kind of visual signature … his hair is invariably disarranged by performance or by the sheer force of personality. Whether he sings or smooches fans or just sits and listens quietly to records in the new ranch house he bought for his parents, long, single strands of hair escape from the network of comb tracks above his forehead to fall forward, over Presley's face."

The effect of Presley's unruly hair, Marling maintains, was to create the effect in still photographs of a "moving body just barely come to rest … In Elvis's case, the trajectory of the swinging, bristling, dangling locks of way-too-long hair became the means by which the still camera conveyed the shock of a live rock performance."

The effect of Presley's unruly hair, Marling maintains, was to create the effect in still photographs of a "moving body just barely come to rest … In Elvis's case, the trajectory of the swinging, bristling, dangling locks of way-too-long hair became the means by which the still camera conveyed the shock of a live rock performance." The author finally gets to the essential question concerning the controversial hairdos sported by Presley and many other young people in the mid-fifties. Were they a sign of "social decadence" or "simply the last frontier between carefree youth and sober maturity?" Marling never answers the question; she merely poses it as one that caused much angst, justified or not, among many adults in the fifties.

Leaving Elvis's hair behind, Marling moves on to his stage clothing. "Big jacket, big pants" outfits, she calls them, designed to permit movement and boost its effect. "His trousers were big," she explained, "especially loose in the hips and legs so that ripples and billows of fabric allowed each twitch of his notorious left leg to register dramatically in the distant recesses of the balcony."

Off stage, Elvis's well known taste for bright, flashy clothes revealed a "fine disregard for impediments to social movement across lines of class and race," according to Marling. It was a short-lived fashion trend, but it appealed to a poor boy who suddenly found himself in the spotlight. Marling explained:

"The 'Memphis Flash' earned his name for styles—black or white styles—that literally flashed across the field of vision like a two-toned Rocket 88 from Oldsmobile: high color contrasts, lots of shiny buckles and buttons, hidden details suddenly disclosed in motion, reflective and textural fabrics that engaged the sense of touch even as they caught the play of light. They were 'Hey, look at me!' clothes, excessive and theatrical … movie costumes for real life, or vice versa."

• The real issue was the way Elvis moved

Of course, Elvis's colorful clothing had little impact in the black-and-white world of television in the fifties. The real issue there was the way Elvis moved. And, ironically, that's what made Elvis a perfect fit for the small screen in 1956. "Presley's 'strip-tease behavior' was particularly repugnant to TV watchers," Marling explained, "because his performance style was, in some perverse way, ideally suited to the new medium. The moving image was supposed to separate television from radio yet much of the standard programming in the 1950s showed static or almost static pictures to illustrate a sound track." Elvis came across as rebellious because he wouldn't stand still. "He both projected and aroused strong emotion through motion. Elvis—the sex-hot, jelly-kneed, thigh-slinging Elvis … "

Marling then comments on Presley's various 1956 TV appearances. She claims that Jackie Gleason saw Elvis as a "guitar-playing Marlon Brando" who would appeal to younger viewers. So he booked Presley on Stage Show over the objections of the Dorsey brothers. "Audience reaction to Elvis's manner and to the new rock 'n' roll music was intense," Marling further contends, "so strong, in fact, that the conservative Dorsey Brothers threatened to walk out if Gleason made good on his intention to bring him back." (Tommy Dorsey biographer Peter Levinson claims the opposite is true; that Gleason didn't like Elvis, and that it was Tommy who supported Presley.)

After Elvis finished his six appearances on Stage Show, he was picked up by Milton Berle, who, according to Marling, was so desperate to prop up his low-rated show, that he "deliberately exploited Presley's unconventional 'dancing' … Packaged to direct attention to Presley's uninhibited movements and their electric effect on female fans, it was the Berle performances that finally brought down the wrath of critics."

• Sullivan tried to soften Presley's image

Marling suggests that Ed Sullivan also wanted to exploit Presley's stage gyrations for ratings before later caving into critics. The author also implies that Sullivan's praising of Elvis in his final appearance was a contrived attempt to soften the edges of the singer's rock 'n' roll bad boy image. Marling argues:

"Sullivan … let Elvis rock his way through 'Don't Be Cruel' and 'Ready Teddy' in full, unobstructed view of the nation's living rooms. But when the critics started again … Sullivan told the cameramen to shoot Presley strictly from the waist up during the last show, on January 6, 1957. And then he told the studio audience what an exemplary young man this quiescent, half-an-Elvis was: 'A real decent, fine boy.'"

Marling summarizes the impact of Elvis Presley's fifties TV appearances as follows:

"Rock 'n' roll and television were made for each other. In dancing blips of light, television registered the bobbing hanks of hair, the swinging jackets, the swiveling hips. Detail wasn't important: on the little living room screen, motion—new, exciting, and visually provocative in its own right—was the distilled essence of Elvishood. In that intimate setting, too, it became double shocking, as if a family friend had begun a series of bumps and grinds in front of the sofa. TV, suggested one cynical Presley-hater, was the real reason teens were so crazy about Elvis; having witnessed their parents' stunned disapproval at close range, over a TV dinner, kids figured he must be worth liking, if only to annoy their elders."

• Fear of Elvis was just an illusion

So, was putting Elvis Presley on television really as dangerous as his critics thought in the 1950s? Marling's implied conclusion is … yes! Why? Well … because people believed he was dangerous. It was a decade of fear in America, and fear became reality. Americans were afraid of Communists, and so for a time believed they saw them hiding everywhere. Americans were afraid of nuclear war, and so for a time taught their school children to take cover under their desks. And some Americans were afraid that Elvis Presley had the power corrupt their children, and so for a time they convinced themselves that he was doing so. Of course, the fear of Elvis was just as much an illusion as those other fears.

Marling closed her chapter on Elvis by returning to the army barbershop:

"The day of his Army haircut … was also the day real rock 'n' roll died. By the time Elvis finished his tour of duty in Germany in 1960, he had lost his edge.He made his first public appearance in a tux on Frank Sinatra's TV special … The hot news was that Elvis's hair now stayed demurely in place when he sang."

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario