Live at the Cotton Bowl …

Elvis's Landmark '56 Road Show

Elvis Presley, singing idol of America's teen-agers and the basis for a nationwide controversy on the gymnastic styling of the current "rock 'n' roll" craze, will make his first Dallas appearance during the State Fair.

Dallas Morning News, October 7, 1956

Dallas Morning News, October 7, 1956

The 71st annual edition of the State Fair of Texas began its 16-day run on Saturday, October 6, 1956. In addition to Presley, other big-name entertainment talent scheduled to appear included Louis Armstrong, comedian Victor Borge, and young pianist Roger Williams.

Presley, however, was the clear leader of the entertainment parade. He was booked into the massive Cotton Bowl for Thursday evening, October 11, normally a low attendance night for the fair. Elvis, though, was expected to change that, with some fair officials envisioning over 75,000 of his rock 'n' roll fans filling the football stadium. Radio station KLIF, sponsor of Presley's Dallas show, plugged his appearance daily with music and contests. Local record shops sold advance tickets for a meager $1.25 for all seats, and Billboard reported the response was "enormous." The admission price increased 50¢ on the day of the show.

"The biggest and most obnoxious Elvis Presley Fan Club in the world is situated here. It has 7,000 members and a pushy president. It also has screaming, squealing loyalty." That was the judgment of William Steif, writer for the San Francisco News, who had come to Dallas that week "to find out what makes Elvis tick."

"The biggest and most obnoxious Elvis Presley Fan Club in the world is situated here. It has 7,000 members and a pushy president. It also has screaming, squealing loyalty." That was the judgment of William Steif, writer for the San Francisco News, who had come to Dallas that week "to find out what makes Elvis tick."

"The biggest and most obnoxious Elvis Presley Fan Club in the world is situated here. It has 7,000 members and a pushy president. It also has screaming, squealing loyalty." That was the judgment of William Steif, writer for the San Francisco News, who had come to Dallas that week "to find out what makes Elvis tick."

"The biggest and most obnoxious Elvis Presley Fan Club in the world is situated here. It has 7,000 members and a pushy president. It also has screaming, squealing loyalty." That was the judgment of William Steif, writer for the San Francisco News, who had come to Dallas that week "to find out what makes Elvis tick."• Elvis discovered staying at suburban hotel

"The arrangements for Presley's arrival in Dallas were a vast mystery," Steif reported in his California newspaper article on October 16. "But the fans busily spied out possible ways of entry, cased hotels, consulted cops and staked themselves out at strategic spots." It turned out that Elvis arrived by train, accompanied by actor friend Nick Adams and cousin Gene Smith. The day before Elvis checked into the Stoneleigh Hotel, his fans were already "flipping in the lobby," according to Steif. The writer supposed Colonel Parker had chosen the quiet, residential inn to keep his boy away from the stresses of downtown Dallas.

It was in a downtown drugstore, though, that Steif asked a "mature redhead with a classic profile" her opinion of Elvis. "He's just a boy," she declared. "Ah'm a woman and he's a boy. But he's so pretty—ah met him once, y'know, over in Fort Worth. He's pretty but he's not sissy, except he's got such tiny hands. Ah wouldn't want mah son to be so pretty, but Elvis is sweet, and he makes his livin' honest."

Teenagers intent on getting the best seats started lining up at the Cotton Bowl in the 90-degree mid-afternoon heat for Presley's 8 o'clock show that evening. "Many wore rock 'n' roll hats—colorful, quick-buck versions of the old port pies," observed Steif, "and lots of 'em wore pink shirts, heavy black skirts or toreador pants with the name 'Elvis Presley' stitched thereon." The swelling crowd included a smattering of teenage boys and older women as well.

Two hours before show time, up to 5,000 were tightly packed up against the Cotton Bowl's front gate . The squealing of young girls alternated with chants of "We want Elvis." To Steif, "It sounded like the Kansas City stockyards."

Attendants slowly opened the gates and allowed the crowd to enter . "The crush and the heat were terrific," Steif reported. "A couple of men jumped on boxes and pleaded with the girls at the rear to stop pushing. That didn't do much good. One little girl, about 13, came through the gates, running and perspiring heavily. She stopped a moment, panted, 'I don't know if it's worth it,' and started running again."

Attendants slowly opened the gates and allowed the crowd to enter . "The crush and the heat were terrific," Steif reported. "A couple of men jumped on boxes and pleaded with the girls at the rear to stop pushing. That didn't do much good. One little girl, about 13, came through the gates, running and perspiring heavily. She stopped a moment, panted, 'I don't know if it's worth it,' and started running again." • Parker relieved when crush at gate ended

After the first rush was over, Colonel Parker, who was standing outside the gates, exhaled, "Whew, they'll be all right now." Then he tucked back inside to attend to the business of selling Elvis photos for 50¢ each and programs for $1. The Colonel had a small army deployed to maximize and keep track of sales. They included his wife, Mr. and Mrs. Oscar Davis, Bitsy Mott, Jason Bevis, Jimmy Rose, and Joe Williams. Also on hand was Presley merchandise manager Hank Saperstein, who came to Dallas to confer with Parker over the test-marketing of the new Presley-label lipstick.

At 8:15 a 90-minute supporting show got underway. Hyman Charnisky and his orchestra provided the music for all the opening acts, which included Sherry Davis, Howard and Wanda Bell, Rex Marlowe, and the Jordanaires. Both reporter Steif and the crowd warmed up to Presley's backup vocal group. "It's a good rock 'n' roll quartet," Steif judged, "and the girls increased their squeals a few decibels to let the singers know they were loved."

While the opening acts performed, Elvis entered the Fair Park Auditorium for a pre-show press conference and lovefest with newspaper, radio and television people, and Presley fan club officials. "Elvis came in, looking sort of sleepy," reported Frank X. Tolbert of the Dallas Morning News. "He said he hadn't gotten but four hours sleep in the last 48."

Tolbert noticed that the fan club girls seemed to be playing a game with Elvis during the press conference. "They'd try to look Elvis squarely in the eye. One pretty blonde reeled back after gazing into the Presley optics and screamed: 'Did you see that look he gave me? Did you see it?'"

Reporters, who were mixed among the fan club members, fired a few questions, and Presley responded:

On his humbleness: "I got sense enough to know where it (fame and money) come from. I know that the Lord can give and the Lord can take away. I might be herding sheep next year."

On the crowds: "I'm nervous in crowds. Sometimes I wish I could get away. Then I get lonesome for the patter of little feet."

On sideburns: "I don't like 'em much, but they've been with me a long time. I just got used to 'em."

After the press finished, Kay Wheeler, 17, president of the Dallas Elvis fan club stepped forward and set off a flash bulb in Presley's face. "Don't burn the sideburns," he yelled. She then presented him with an oil portrait and some cuff links. "He's different," she later told reporter Robert Ford of Presley's allure. "The younger generation needed something different. We needed him."

• Wave of light escorted Elvis around the Cotton Bowl

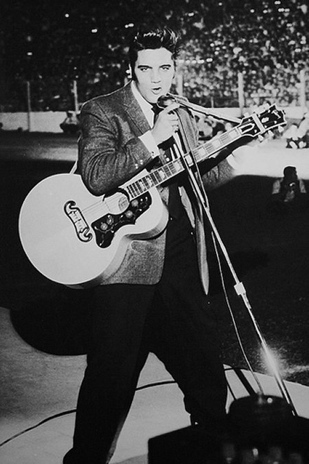

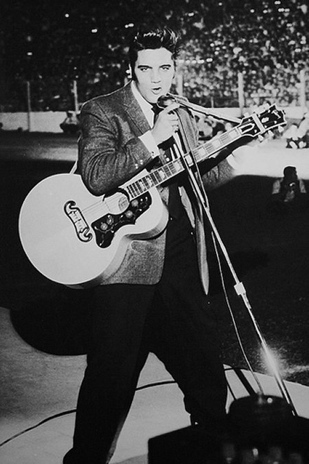

A brief intermission followed the opening program. Then the stadium darkened, and Elvis made his entrance in an open Cadillac with a spotlight following his progress around the field. Flashbulbs created a wave of light as Elvis passed each section of the grandstand. The car pulled up in front of the stage straddling the 50-yard line, and Elvis jumped out and ran up the steps.

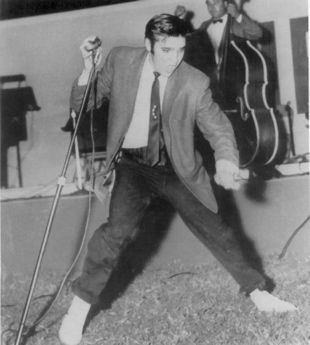

"Elvis … took the microphone and started to say something," reported Steif, "but you could never figure out what he was fixing to say because the girls in the stands kept hollering." Presley, who Tony Zoppi of the Morning News described as "weirdly handsome," was dressed in a green tweed jacket, a blue tie, a white silk shirt with pleats, charcoal trousers, a black and gold cummerbund, and white buckskin high-topped shoes with red heels.

"Elvis … took the microphone and started to say something," reported Steif, "but you could never figure out what he was fixing to say because the girls in the stands kept hollering." Presley, who Tony Zoppi of the Morning News described as "weirdly handsome," was dressed in a green tweed jacket, a blue tie, a white silk shirt with pleats, charcoal trousers, a black and gold cummerbund, and white buckskin high-topped shoes with red heels.

"Elvis … took the microphone and started to say something," reported Steif, "but you could never figure out what he was fixing to say because the girls in the stands kept hollering." Presley, who Tony Zoppi of the Morning News described as "weirdly handsome," was dressed in a green tweed jacket, a blue tie, a white silk shirt with pleats, charcoal trousers, a black and gold cummerbund, and white buckskin high-topped shoes with red heels.

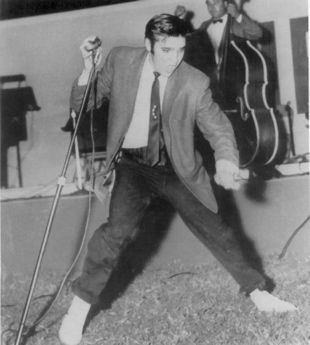

"Elvis … took the microphone and started to say something," reported Steif, "but you could never figure out what he was fixing to say because the girls in the stands kept hollering." Presley, who Tony Zoppi of the Morning News described as "weirdly handsome," was dressed in a green tweed jacket, a blue tie, a white silk shirt with pleats, charcoal trousers, a black and gold cummerbund, and white buckskin high-topped shoes with red heels."Presley started off with Heartbreak Hotel," Tolbert noted in the Morning News the next day, "doing a staggering, shuffle-footed dance with the microphone. Sometimes, he went into a really classical Indian war dance. Other times it was sheer voodoo acrobatics as he threw his famous pelvis from the 50-yard line to the 35."

Presley's voice was lost in the continuous din produced by his feminine admirers, noted Tolbert, adding, "If that earthquake-recording machine at SMU didn't register the Elvis Presley disturbance in the Cotton Bowl, then they'd better swap it in for a new one … At his first appearance those incredible, high-pitched, ear-splitting screams began and never let up." Steif thought the noise was geography-appropriate. "It's a good thing Texas is so big," he noted. "The volume of shrieks that welled up out of the bowl might have scared the residents of a little-bitty ol' state."

When Elvis tore into "Long Tall Sally," Zoppi likened his pelvic gyrations to a "cross between an Apache war dance and a burlesque queen's old-fashioned bumps and grinds." In his AP article on the event, Robert Ford noted that, "With each whisper from the rock 'n' roll voice the shouts of the multitude drowned out the song. The sound of 26,500 voices vibrated around the bowl when Elvis went into his peculiar knee-twitching, hip-swinging dance to accent pauses in the music." Steif proclaimed, "Never in the history of show business has an entertainer released so many inhibitions publicly."

A security force of 95 policemen patrolled the bowl, which was in the dark except for the stage. Some officers walked through the crowd, shining lights in the faces of those standing up and waving arms or seeming to be having paroxysms in the aisles.

• Photographers caught images of strained faces in crowd

"The photographers ran around like panting hound dogs," observed Tolbert, "sometimes shooting into the crowd behind the 8-foot-high restraining fence with these brief flashes of light showing you the strained faces of young girls. Some of them had screamed themselves so hoarse that they could only sit and weep and moan."

The promoters' vision of all the Cotton Bowl's 75,504 seats being filled was far from realized. Still, the crowd, which gathered on the eastern side of the bowl, was the largest ever to see an entertainer in Dallas. Both Gordon McLendon of sponsoring radio station KLIF and State Fair ticket manager Arthur K. Hale estimated the crowd at 26,500 paid customers. Variety used the same crowd count in its October 17 issue. That number made the Cotton Bowl crowd that Thursday evening in Dallas the largest audience to see a Presley stage show in the 1950s.

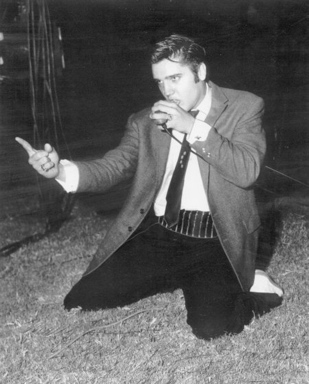

Steif described how Elvis delivered his standard finale:

Finally, after a half an hour and seven or eight of his standard numbers, he wove into 'Hound Dog' and bounced off the stage, carrying the mike with him. There, on the 50-yard-line, he sank to his knees, rose, wove, bumped, ground and sank again, time after time. The girls screamed themselves silly. If may have been obscene, but if so it was obscene in the same way the climax of a revival meeting is obscene.

Elvis worked himself over to the grass alongside the stage, sank almost out of sight and suddenly slipped into the waiting Cadillac. A motorcycle cop roared out in front, the car drove off and quickly the bowl's overhead lights were turned on. The shrieks became groans of disappointment. But the ball was over, the spell was broken. Noisily, the fans began filing out of the stadium, spent.

The convertible spirited Elvis back to his suite at the Stoneleigh, where later that evening Steif found two teenage girls sitting in the lobby. One told him, "We got up at 3 o'clock this morning and flew from Stamford, Texas—that's 250 miles away—to see Elvis." The other girl added, "He promised he'd come down and talk to us." Steif closed his newspaper article with the confirmation, "And sure enough, he did."

Alan Hanson

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario