Gray, however, did not like being stalled. By now, she'd waited more than 30 years for an answer, having contacted Wertheimer by phone in the late 1970s when she was Barbara Satinoff, living in Royersford, Pennsylvania, with her third husband and running halfway houses for recovering addicts. By her account, Wertheimer blew her off. Though Wertheimer says he has no recollection of the conversation, Bobbi says she remembers plenty.

"I want to write a book about my life and all the people I've been connected to in show business," she told him, alluding to the days she'd dated two of Liberace's boyfriends in Puerto Rico, got in a fight with Zsa Zsa Gabor while doing makeup for The Mike Douglas Show, and worked for Frederick's of Hollywood. While the Elvis episode was only "one tiny little dot" of her colorful past, she said, she wanted copies of Wertheimer's pictures to illustrate it.

Gray's background, by any measure, reads like something out of an Erskine Caldwell novel. A self-described "free spirit," she was the illegitimate daughter of a factory worker and a cop whom, she says, would occasionally beat her. When she was 12, her boyfriend raped her. By 14, she had run away to marry a kid named Harry Wright, with whom, at 16, she had a daughter, Debbie. A year later, she was divorced and doing a little hustling. "I was a pretty loose gal," she admits. "Then I started waking up to the fact I was a whore."

Gray did some nude modeling to pay the bills, caught the eye of performers who would swing through Charleston on the big-band circuit, and accepted a ride to Atlanta from Woody Herman's road manager. Settling there, she worked for a record-distribution company and started dating the singer Tommy Leonetti, soon to star on TV's Your Hit Parade. Come 1956, she left her young daughter in the care of friends and returned to Charleston, taking up so-called "show-off" dancing at a club called the Carriage House—right around the time that Elvis came to town.

None of this ever came up during that long-ago phone call. Not that Wertheimer, in Gray's estimation, gave her much of an opening.

"A lot of women have called and said they are that girl and they are not," she remembers him saying.

"Well, I am."

"Do you still have those earrings?"

"No."

"What about the pocketbook with the fake pearls?"

"Are you kidding me?"

"Well, why not…?"

"I've moved back and forth across the country!"

Then came another test. "Elvis was on his way to do a TV show. What was it?"

"I guess Ed Sullivan."

"No, see, you're not the girl. If you are, how many people were in the cab to the theater?"

"There were six."

"No . . . There were five. Can you tell me this? What do I look like?"

Bobbi had reached her breaking point. "You're a fat little Jew with a bald head, and you wear glasses," she snapped, not really remembering what he looked like behind his camera. Her Jewish husband laughed as she hung up the phone. The bespectacled Wertheimer stands five feet seven but, to this day, has a full head of hair.

Amonth after receiving Gray's Facebook message, Wertheimer still had not responded. Frustrated, she called in to Richard Todd, a D.J. promoting an Elvis tribute show on WTMA, a local radio station. Identifying herself only as Barbara on James Island, she insisted she'd kept a secret since 1956, declaring herself the girl in the classic kiss picture.

"Do you know this is you for a fact?" the D.J. asked.

"Oh, absolutely."

One listener, however, had his doubts. Broadcast veteran Ron Brandon had recorded Presley's homecoming concert in Tupelo, Mississippi, when Brandon was a 17-year-old engineer at WTUP radio. He got suspicious when the caller mispronounced the name of the Mosque Theatre. But after they finally connected in person, she won him over, and Brandon, in turn, got in touch with me. He thought I might be able to authenticate her story since I'd just published a book the month before on Presley's love life, Baby, Let's Play House.

When Elvis Presley came to Charleston in the summer of '56, Gray had never heard of him. But one night at a bar her rowdy companions were all fired up about Presley, saying he played "nigger" music, and guessing he was "sweet" because he wore mascara. "He's staying up in the Francis Marion Hotel," one friend said. "Bobbi, you ought to call him. You could get a date with him. If anybody could, you could."

As Barbara tells it, she was drunk that evening and accepted the dare, wobbling a little as she picked up the phone behind the bar, and asking the hotel operator to put her through to Presley's room. His oddball cousin Gene Smith supposedly answered.

"Is this Elvis?" she asked.

"No, do you want to talk to him?"

"Yeah, I want to talk to Elvis."

Soon, the rock star and the stranger were into it, flirting for a good half-hour, before making plans to meet two days later in Richmond, Virginia—425 miles away—once Presley returned from a New York rehearsal for a TV segment on The Steve Allen Show. From Richmond, Gray made it perfectly clear, she would then head north to see her boyfriend in Philadelphia. Before hanging up, Gray recalls, Presley promised to send a car to collect her the next day.

"I said, 'O.K.,' thinking it was just a line." But the next morning Gene and a buddy, who introduced himself as Elvis's road manager—today no one in Presley's camp can seem to place him—showed up in a '56 ivory-colored Cadillac Eldorado Biarritz that Elvis had purchased earlier that month. The trio drove to Richmond, where Gray stayed at her Aunt Gladys's house. Gray's cousin Ruth Wagner, who was living there at the time, remembers the car, the overnight visit, the excited talk about Elvis.

The following afternoon Bobbi met Gene outside the swank Jefferson Hotel. Carrying a bright-green jacket in a plastic dry-cleaning bag—Elvis's change of clothes for that night's second set—Gene walked her through the lobby and into the coffee shop, where his cousin was finishing a bowl of chili. Bobbi still had no idea what the singer looked like.

"Elvis, she's here," Gene said to the pompadoured man sitting at the counter, wearing a white shirt and matching knit tie that set off his slate-gray suit. "He turned around," Bobbi remembers, "and that was the first time I ever laid eyes on him. I thought, God, he's beautiful."

Elvis never stood up, but motioned for Bobbi to sit on the vinyl chair next to him, and then gave her a hug before angling closer.

Despite appreciating his androgynous good looks (and his white buckskin shoes), Bobbi was a big-band follower and a Frank Sinatra fan; her tastes in men followed a similar sophistication. She says she considered Elvis little more than a budding musician—"and really kind of insecure." It put her off that he asked her who she was and where she was from, like they'd never had that first phone conversation. And his Mississippi accent made him seem like "a goofy guy from the sticks." She found his long sideburns, which were radical for the day, sort of weird, and thought they anchored him in the blue-collar world (which he'd recently inhabited as an apprentice electrician). For her part, she never mentioned she was a divorcée with a child—which would have been the ultimate turn-off for the virgin-obsessed Presley.

Al Wertheimer, who had followed Elvis to Richmond, documented the next moments as Elvis attempted to loosen up his date. Bobbi was oblivious to the photographer and the two black Nikons dangling around his neck.

"Would you like something to drink, a beer maybe?" Elvis ventured.

The question threw her. A coffee shop serving beer? Maybe this was just a test. "No," Bobbi declined.

"That's good," Elvis said, "'cause I don't let my women drink."

"I'm not your woman," Bobbi snipped.

"Do you smoke?" Elvis pushed.

"No," she fibbed.

"Good. I don't like my women to smoke, either."

"I told you I'm not your woman.… If I want to smoke and have a beer, I'll do it."

Bobbi had his attention; Elvis liked a girl with attitude. He showed her his script for The Steve Allen Show, but she still seemed unimpressed, so he got right up on her ear, alternately whispering and shouting. She mustered a smile or two, which brought out his playful side. It was now a half-hour before his five-o'clock performance. Gene interrupted to say they had a cab waiting for the half-mile ride up Main Street to the yellow-brick Mosque.

"Come on," Elvis said. "You're going to be with me for the show." As they got up to leave, Elvis suggestively grabbed his new friend, which sent her running out the side door of the hotel and into the street, Elvis in pursuit and calling her "Fat Butt." She liked him better now.

It was in the taxi that Bobbi first noticed Wertheimer, who climbed in the front seat with Gene and the cab driver. In the back, Elvis anchored one side of the seat, while Junior Smith (Gene's spooky-looking brother, a Korean War vet) held down the other. Bobbi squeezed in between, and Elvis, clowning around, followed the photographer's directive to look animated. He messed up Bobbi's hair. He pretended to choke her. But what Wertheimer really wanted was something intimate. A nuzzle, an embrace, a kiss.

When the cab reached the Mosque, Elvis, with Al on his heels, got out at the stage entrance to talk with the fans, while Gene and Junior took Bobbi around to the front of the hall. There was hubbub backstage as the supporting acts—the Flaim Brothers Orchestra, comic Phil Maraquin, and magicians George and Betty Johnstone—performed. Elvis paused to pull out a cardboard can of Royal Crown pomade and sculpted his dirty-blond hair into a high, goopy wedge. Then he called for a quick rehearsal with the Jordanaires, his backing vocal group.

After a while, Wertheimer noticed his main subject was missing. Concerned, he made his way down the fire stair to the stage level, and at the end of a long, narrow hallway he saw two figures in silhouette—Elvis and the girl, as he would call her. They were wrapped around each other now, with Elvis intent on a kiss. Wertheimer remembers, "I asked myself, Do I interrupt these love birds, or do I leave them alone? I finally thought, What the heck? The worst that can happen is that he'll ask me to leave."

Wertheimer climbed up on a railing and scissored his legs for balance. He was now four feet from the girl, shooting over her shoulder, more or less into Elvis's face. Through his viewfinder, the scene was illuminated by harsh backlight from a nearby window and a 50-watt bulb overhead.

The pair paid no attention as he steadied his breathing for a shutter speed around a 10th of a second. Elvis pulled his date closer now—his hands clasped around her back, her hands resting on his shoulders. Then he gave her the smoldering stare he'd copped from Rudolph Valentino, his early idol.

Wertheimer, desperate to light them from the other side, put on a maintenance man's voice—"Excuse me, coming through"—as he squeezed past, descended three steps below them, and set his frame. It was then, he claims, that the girl taunted, "I'll bet you can't kiss me, Elvis."

"Of course, Elvis has been trying all day to kiss her, and he comes back and says, 'I'll bet you I can.' She sticks out her tongue a little, and he comes in and meets her tongue with his, but he overshoots the mark and bends her nose. Then he backs off a trifle and comes in a second time—perfect landing."

'That's a bunch of crap," says Gray. "I never said, 'I'll bet you can't kiss me.' I might have said, 'You can't kiss me, because I have a boyfriend and I will not kiss you.' But right after that, I pulled away from him, and he chased me across the stage trying to kiss me, just before the show started."

Not only did she not notice Wertheimer in the hallway, but she doesn't remember seeing him the rest of the evening. After the second show, Bobbi and Elvis got in a car—maybe a sheriff's paddy wagon—to go to the train station. Elvis was headed back to New York and wanted Bobbi to go with him.

"I said, 'No, I've already made plans. I'm going to Philly.'" But Elvis insisted. They climbed aboard Car 20 of the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad train and made their way to Elvis's private compartment, Roomette No. 7. There, Elvis intended to get what he'd wanted all along.

"He started grabbing me and hugging me, and I finally let him kiss me. Somehow we ended up lying on the bed, and he tried to feel me up. He put his hand on my behind and he said, 'Oh, you've got on a girdle.' I said, 'They're elastic panties, but what's it to you?' He said, 'I don't mess with girls who wear girdles.' And he stopped." Suddenly, somebody knocked on the door and warned, "Elvis, the train is leaving." And Bobbi said, "So am I."

In Richmond, Wertheimer accompanied Elvis's party on the train up to New York, but he doesn't remember Bobbi being anywhere near it. Nor does she show up in his pictures of Elvis in between shows, when the singer gave an interview to a local reporter, Gene Miller from The Richmond Times-Dispatch.

"I was standing there talking with the Jordanaires and goofing off with the Flaim Brothers," she explains. "I spent more time with the other guys than I did with [Elvis]." (Miller, in fact, would corroborate part of her tale, at least, writing that Elvis "playfully chased an attractive young blonde across the stage into the wings.")

One man can attest to other aspects of Bobbi's story. Edward Swier, her Philadelphia boyfriend, now 79 and a retired Boeing engineer, remembers her visit that summer. (So as not to upset him at the time, she didn't disclose her dalliance with Elvis.) "We were pretty hot and heavy for a couple of years," says Swier, who met her over a game of miniature golf when he was stationed at Charleston Air Force Base. "She was quite a live wire and a very striking girl. She showed me some nude photographs of herself in a magazine. I remember she got a call from Pat Boone, because I answered the phone. He wanted to take her to dinner and she turned him down."

Boone would play a much bigger role in her life, leading her, as Bobbi puts it, "from a loose girl to a child of Christ." In the late 60s, Boone and his wife, Shirley, baptized Bobbi, she says, in their swimming pool in Beverly Hills. Now 75, Caroljean Root, with whom Bobbi lived at the time, and who heard her Elvis story long before "The Kiss" began appearing on souvenir tchotchkes, remembers the Boone connection vividly. "She would go over to Pat and Shirley's house, and also attend religious services with them. Even after she was baptized, they were still in communication. They were all friends."

Boone, now 77, hosted Bible-study sessions in the early 70s for celebrities, Elvis's wife, Priscilla, among them. Boone did not return Vanity Fair's repeated calls. In 1970, he wrote a book, A New Song, in which he admitted to flirtations on the road that nearly upended his marriage: "An occasional drink, the loud music, and the titillating awareness that some young lovely was obviously 'available'—all seemed more and more fun." If she ever writes her own book, Bobbi, an observant Baptist, hopes it "will show young girls how Jesus can save you from anything and everything."

So, after all the shake, rattle, and roll, where's the proof?

Some of Bobbi Gray's recollections are too minute for casual invention. Many die-hard Elvis fans don't know about the Flaim Brothers, for instance; they don't show up in Peter Guralnick's authoritative biography, Last Train to Memphis. They are, however, billed in advertisements for Presley's 1956 shows, and toured with him for a year, according to Emil Flaim, now 78.

Most significantly, though, is the fact that when Vanity Fair asked Bobbi for snapshots of herself from the same era, photo after photo seemed the spitting image of the woman Wertheimer shot as Elvis cozied up to her in the cab that day. In addition, the picture on Bobbi's 1974 driver's license is also a perfect match—as are her signatures, then and now.

By the time Wertheimer got around to answering Bobbi's e-mails ("Before we talk about it too much, I need to know exactly how tall you are in your bare feet"), Vanity Fair was acting as an intermediary, showing Wertheimer Bobbi's old photos ("They're good—they're very close"). Then came the detail that really piqued his interest. Told that Bobbi was four feet eleven, Wertheimer caught his breath: "Is. She. Really."

It was then that Wertheimer got nervous. "After 55 years, she hasn't said boo, and now she's finally coming out of the closet?!"

Last spring, Gray and Wertheimer finally spoke on the phone, and Wertheimer quizzed her relentlessly. For more than an hour, they bantered and sparred, but not without cordiality and humor.

Al: Have you felt badly that you haven't really gotten the recognition that you should have had as one of Elvis's lovers?

Bobbi: Listen, Al, I never was his lover.

Al: I'm not here to upset you. I'm here to try to do some fact-finding.

Bobbi: This is what you did back in the 70s. You annoyed me to no end, and that's why I never called you again.

Al: In the second show, [Elvis] had a very bright-colored jacket on. Do you recall the color?

Bobbi: No, because when I saw the jacket, it was [in a dry-cleaning bag].

Al: But you're now in the theater. The show is finished, and he's changing his clothes to the second show. What was he wearing?

Bobbi: He could have been in his drawers for all I know.

Al: [Laughing.] He wasn't in his drawers. He was nude.

Bobbi: Oh, God . . . I think I remember an awful lot for a 74-year-old lady.

Al: See how much I remember for being an 80-year-old codger?

Today, Wertheimer concedes that Bobbi is, in fact, the Kiss Lady. What convinced him, he says, apart from her height and her personal photographs from the time, was what she said about the taxi ride to the theater—one of the points she had tried to make in their 70s phone call. "I said, 'Three of us in the front? I don't recall three in the front.' She said, 'Well, if you notice in one of your pictures, there is an elbow sticking out. That belonged to the other cousin."

And Bobbi had remembered something else that Wertheimer had not, a detail that had been partly visible in the photographs all the time: Junior was holding . . . Elvis's guitar!

"I have been looking at my photographs for 54 years," says Wertheimer, "and I didn't notice [the edge of the guitar case]. So her memory was, in that case, better than mine."

Last summer, he offered her a settlement: $2,000 and his public acknowledgment—he has signed an affidavit—that she is, indeed, the woman in his famous frame. Additionally, he pledged to provide nine autographed copies of two of his Elvis books, three signed prints of "The Kiss," six signed posters, six magnets, and, on a perpetual license, 24 digital files of her photographs for any personal projects.

At first, Bobbi wanted him to donate funds to her church, but Wertheimer balked. "If I were richer I might pay her more. But she wants to be a celebrity. Of course, she might feel that she's been had, but on the other hand, had I not been there … It would have been a non-event. She is such a church-going person, well, let her hustle a little bit. If she wants to go on Elvis cruises and talk about being the 'Tongue Lady' and sell some of the prints that I allow her to make, she has my blessings."

In the end, after months of negotiation, Bobbi signed the agreement, giving up all commercial rights to one of the most desired photos in rock 'n' roll.

To decompress, she made a trek to Richmond to revisit the old Mosque Theatre and another to Washington, D.C., to see Wertheimer's show at the National Portrait Gallery. Her hope was to be photographed in front of "The Kiss" as a memento for her three grandchildren. But when she arrived, she didn't bother to go in. The crowds were overflowing.

Today, Barbara Gray insists she's after neither money nor fame—just a glimmer of recognition, which is, after all, what many of us seek in this life. "I didn't get into this to be frustrated and crazy. I just wanted to get my name on the damn picture."

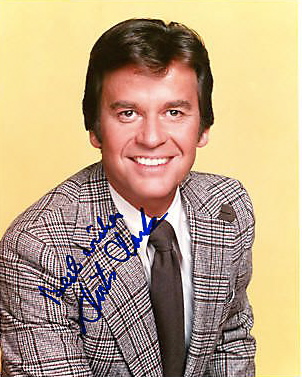

At age 28, Dick Clark was hosting a local TV dance show in Philadelphia in April 1957, when Elvis Presley brought his stage show to town. It's very possible that the two men met at that time, as DJs and TV hosts were invited to Presley's press conference in the city. It was just four months later that Clark soared into the national spotlight when the ABC television network picked up his show, renamed it American Bandstand, and began airing it nationally on August 5, 1957.

At age 28, Dick Clark was hosting a local TV dance show in Philadelphia in April 1957, when Elvis Presley brought his stage show to town. It's very possible that the two men met at that time, as DJs and TV hosts were invited to Presley's press conference in the city. It was just four months later that Clark soared into the national spotlight when the ABC television network picked up his show, renamed it American Bandstand, and began airing it nationally on August 5, 1957. During the first interview in February 1959, Clark asked Elvis if he had been working on his music. Presley assured Clark that he was. "I have a guitar up here in the room," he explained. "I don't want to get out of practice if I can help it." Clark then supplied evidence that Elvis's popularity had not slipped at home. "In the annual American Bandstand Popularity Poll you walked away once again with a couple of honors this year," Clark announced. "The Favorite Male Vocalist Award and the Favorite Record of 1958. The kids voted you top man all around."

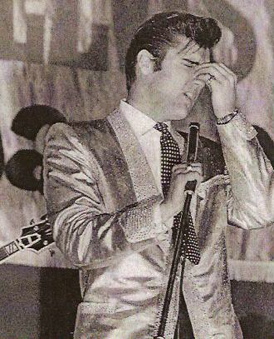

During the first interview in February 1959, Clark asked Elvis if he had been working on his music. Presley assured Clark that he was. "I have a guitar up here in the room," he explained. "I don't want to get out of practice if I can help it." Clark then supplied evidence that Elvis's popularity had not slipped at home. "In the annual American Bandstand Popularity Poll you walked away once again with a couple of honors this year," Clark announced. "The Favorite Male Vocalist Award and the Favorite Record of 1958. The kids voted you top man all around."  Elvis's appearance in Portland on Labor Day, September 2, 1957, was one of his final concerts of the decade. By then he was no longer the wild, raw performer he had been the previous couple of years. Instead, he had polished his act. He had become a master at manipulating a crowd's emotions, and he was drawing the biggest crowds of his (or anybody else's) career. With a string of hit records in his repertoire, he was truly at the top of his game.

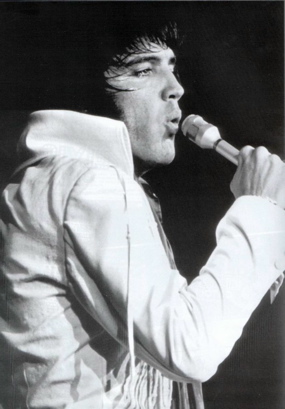

Elvis's appearance in Portland on Labor Day, September 2, 1957, was one of his final concerts of the decade. By then he was no longer the wild, raw performer he had been the previous couple of years. Instead, he had polished his act. He had become a master at manipulating a crowd's emotions, and he was drawing the biggest crowds of his (or anybody else's) career. With a string of hit records in his repertoire, he was truly at the top of his game. There was also a striking difference in Elvis's stage deportment during the two Portland concerts. It was gyrations versus karate. In 1957 an Oregon Journal writer characterized Elvis's stage act as a series of "bumps and grinds, wiggles and sinuous writhings." According to the Oregonian, in 1970 Elvis still worked up a sweat, but "many of his movements [were] unnecessary; he [directed] the band with arm jerks; he [ran] around the stage like a long-haired Pagliacci eager to keep the stage crew happy."

There was also a striking difference in Elvis's stage deportment during the two Portland concerts. It was gyrations versus karate. In 1957 an Oregon Journal writer characterized Elvis's stage act as a series of "bumps and grinds, wiggles and sinuous writhings." According to the Oregonian, in 1970 Elvis still worked up a sweat, but "many of his movements [were] unnecessary; he [directed] the band with arm jerks; he [ran] around the stage like a long-haired Pagliacci eager to keep the stage crew happy."